Baker Perkins Historical Society - Virtual Books

BAKER PERKINS AT WAR

EPILOGUE

INDEX

Much of the information provided in this Epilogue can be found by following the links in the main section of this "book". However it is felt that the efforts made by Baker Perkins in developing automatic bread plants through two World Wars justify closer focus as they could be considered to be more in line with its "Quaker" image. (See also Mobile Field Bakeries - below).

There follows a brief account of the development of equipment for:

"Feeding the troops - developing the military field bakery."

Joseph Baker & Sons became established in England with the move of Joseph Baker and his family from Canada in 1878, Angier March Perkins, the second son of Jacob Perkins, was 21 when, in 1821, he sailed from America with the rest of his family to join his father, Jacob Perkins. Both families recognised the opportunity to mechanise the baking business. Later, when Angier had to step in to rescue the Perkins business to counter his father's profligacy, the scene was set for some healthy but at times bitter, competition.

One of the key driving forces behind the Baker family's efforts was their determination to improve the lot of the baker. J. Allen Baker visited many bake houses and was horrified by what he witnessed: "Night baking with intolerably long hours, the workers sleeping in their kneading-troughs, the kneading done with bare feet, no proper ventilation or sanitary arrangements, cockroaches, mice and sometimes even rats In untold numbers". He saw these things as being as dangerous to the public as they were to the workers and resolved to improve conditions by introducing machinery into the confectionery and baking industry.

BEFORE MECHANISATION - THE "ALDERSHOT" OVEN

These two images might suggest that the conditions experienced by the military were at least as daunting as J.Allen Baker had experienced in the civilian bread baking business of nineteenth century London.

A GERMAN M0BILE BAKERY IN WW1

Feeding soldiers in action, often under very adverse conditions, as these images suggest poses many problems for the military. Soldiers on active service require large volumes of food that is nutritious and palatable, prepared and delivered under hygienic conditions. The final stage of delivery to the soldier in the front line clearly creates particular problems. It has been said that in WW1 it could take up to eight days before bread reached the front-line and so it was invariably stale. Fortunately, bread has many of the desired characteristics. The type of bread required on active service has been described as -

"Apart from being palatable, the shape, crust and texture must be such as will resist the rough handling such bread receives during transport to the troops in action. Experience has shown that a 2-lb, 7” square loaf about 4” high with a reasonably heavy crust and not too open a texture, will withstand this rough handling. The most expedient way of producing this loaf is to bake them six in a pan measuring 20½” x 13½”. In manually producing this loaf, it is only necessary to divide, hand up into a ball, and set them on the trays for a final proof".It is generally thought that all troops had to exist on the same meagre rations, such as army biscuits and bully beef, made bearable by gifts from home. However, those fighting in northwest Europe in WW2 fared much better. Fresh and chilled meats were widely available as were fresh vegetables. Troops often did not have the luxury of fresh fruit and eggs were of the powdered variety, which was also in short supply. Mail, tea and cigarettes were supplied from home.

The men huddled in their trenches in WW1 were less well served. The men at the Front considered the rations to be "appalling", particularly the hated "Maconochie" - a thin stew of unrecognisable meat and vegetables,. barely edible when hot and "disgusting" when cold. Instead of bread there were biscuits produced by Huntley & Palmers and teeth crackingly hard unless first soaked in tea or water."The soldiers in the trenches didn't starve but they hated the monotony of their food," says Dr Rachel Duffett, a historian at the University of Essex. "They were promised fresh meat and bread but the reality was often very different." (With acknowledgements)

Andrew Robertshaw, a curator at the Royal Logistic Corps Museum, in Camberley, Surrey, and author of "Feeding Tommy", says: "There was no Army catering corps and in the trenches the men fended for themselves. But away from the frontline there was a cook for about every 100 men. (With acknowledgements)

NOTE: The logistics of delivering nutritious food in the form of "combat rations" to men under fire is a fascinating and complicated subject in its own right that, should you be so inclined, can be sampled simply by "Googling" - Feeding the Troops. We have been unable to uncover any relevant activity by Baker Perkins group companies unless one includes the suggestion that the hard biscuits made under War Office contract by Huntley & Palmers were in fact made on Baker Perkins equipment. This narrative therefore will confine itself to the role played by Baker Perkins in developing automatic bread plants.

The involvement of Baker Perkins in the baking industry can be traced back to a significant event (see here) which resulted in Angier Perkins taking out a patent in 1851 for a wrought-iron tubular system for circulating hot water in ovens. Most of these ovens were bought for baking bread for the army at home and overseas, more than seventy per cent of sales being to the military authorities. In these early days of oven manufacture, Perkins helped to feed more soldiers than civilians. (See - "Bread Oven Technology").

With the success of Angier Perkins' ovens, the race was on to develop a completely automatic bread plant by mechanising the highly labour-intensive dough preparation process. Fortunately, two men of genius were working on this problem - John Pointon collaborating with the Perkins' business and John Callow, a man who, like John Pointon, was driven to improving the lot of the baker in the second half of the 1800s, working with the Bakers on their ‘Patent “New Process” Bread Making System’. For an evocative description of the trials and tribulations experienced by John Pointon and his father whilst developing his dough divider and getting it accepted by bakery managers, see here). To understand the significance of John Callow's achievements - see "Bread Making Machinery Development.

Later, after much experimentation, John Callow was able to develop a process of automatic dough-dividing and by 1903, the Pointons had designed a machine to mould dough for bread making. The development of a device to mechanise the rest period required by the dough to recover and rise took much longer and resulted in a swinging tray prover. This formed the link between the ‘Universal’ mixer and kneader and the steam oven. (See also here).

The application of the genius of both John Pointon and John Callow to solving this problem led to a periodof intense cut-throat price competition between the two companies, during which the Baker company was accused on two occasions of patent infringement.The ramifications of this dispute were both prolonged and far-reaching (see"The Background to the Merger"and "Patent Infringements").

A British Army Base Bakery of WW1 would have looked similar to this German example. So far we have been unable to locate a relevant image of a British Base Bakery of the time but the number of men required to support those in the front line is obvious. What is not shown is the large number of men making-up and preparing the dough for these men to load into the ovens, until the end of WW1, a laborious task carried out entirely by hand.

E.H.

Gilpin (Senior Director of Joseph Baker & Sons), had calculated

that the use of large automatic bread-baking equipment would release

20,000 of these men for fighting. (see here). Soon

after the outbreak of hostilities, Gilpin embarked on the long and

arduous process of beating on as many doors in the War Office as possible

to argue his point. His persistence finally rewarded, he was asked

as a matter of urgency to set up a demonstration as soon as possible

and, for speed, the Baker directors decided to invite Ihlee to come

in: he jumped at the chance of collaboration.

The new plant, made partly at Willesden and partly at Peterborough, was

ready in twelve weeks for the officials from Whitehall to inspect. A

contract was drawn up between the War Office and Joseph Baker & Sons,

and the Bakers entered into a sub-contract with Peterborough. The two

firms divided the manufacture, Perkins being allotted the mixing machines,

final moulders and draw-plate ovens, while the dividers, the first moulders

and provers were turned out at Willesden. The complete unit was named

the Baker Perkins Standard Army Bread Plant. (For a description of the

equipment installed in a British Base Bakery see "Static

Field Bakeries" below).

Muir, in his "The History of Baker Perkins"; tells us:

"Installations were made in England and at the base bakeries at Rouen and Boulogne. Eventually, the whole of the British Army on the Western Front was dependent on these bakeries for bread. The Americans in France became interested and soon Baker and Perkins were erecting for them, at Dijon, baking plant that turned out a million rations of bread per day. Herbert Kirman thus found himself in charge of all of the military bread plant on the Western front. After recovering from his wounds, Major Joseph S. Baker was appointed Inspector of all military baking equipment".This coming together of Perkins Engineers Ltd. and Joseph Baker & Sons Ltd. in their war effort could not have been more propitious. If any single step could be called the crucial one in the union of the two firms, it was the request from the Baker board that Ihlee would collaborate in the Army bread plant.

By May 1915, field bakeries began to be equipped with Perkins steam-pipe ovens - the bakery at Calais having 39 Perkins ovens by 1916 - and in the larger bakeries, machinery was introduced for mixing, dividing, scaling and moulding. However, some bakeries remained as hand-bakeries equipped with army-type Perkins Field ovens.

In January 1918, members of the British Women's Auxiliary Army Corps were introduced to the Rouen bakery - a process aimed at freeing more men for front-line duties. The women were used on the dividing and moulding machines - usually Baker Callow dough dividers and umbrella pattern Perkins dough moulders.(See here)

Static Field BakeriesIt was due to the success of the Standard Army Bakery Plant, (see History of Joseph Baker Sons & Perkins), that it was decided, at the beginning of World War II, to establish three large Static Machine Bakeries in France, to be used in conjunction with the well-known Mobile Bakeries. However, due to the rapid fall of France in 1940, they were never built and it was not until 1943, that they were commissioned in England. The machinery, supplied by Baker Perkins, had been allowed to rust at Sir Moore’s Barracks, Shorncliffe, near Folkestone, Kent, in the three and a half years between 1939 and 1943, before being installed and brought into use at three sites – at Newchapel, Surrey, Danesbury Park, Welwyn, Hertfordshire and at Leaton, near Shrewsbury, Shropshire.

The equipment comprised of, one flour plant, two 2 sack-sized ‘Viennara’ dough kneading machines, one sack cleaner, two reciprocating head single pocket dividers and conical hand-ups, one four piece pocket prover, one ‘Z’ Type conical moulder and five double-decker, oil-fired, drawplate ovens. The ovens had separate furnaces, fuelled by oil, which heated water, the steam being conveyed along sealed pipes to provide the heat. Having separate furnaces enabled each baking chamber to bake at different temperatures, if required. Each oven held ninety-six Quartern loaves per deck, eight loaves wide and twelve deep, the loaves taking about forty-five minutes to bake. The equipment was typically housed in a series of corrugated iron huts, three short huts on one side for storing flour and other ingredients and two very long huts on the other housing the ovens and make-up equipment and bread store. During the war, deliveries of flour and other ingredients were made under the cover of darkness, to prevent detection by enemy aircraft, with the Bakery buildings being large enough to accept the delivery lorries being reversed into the building to be off-loaded out of sight. (See also here.)

It is interesting to note that the Static Bakery at Welwyn was the first to employ ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service) female bakers, later to be superseded by WRACs (Women’s Royal Army Corps), RASC personnel being used only for heavy work and to administer the unit. The numbers employed in each bakery varied from fifteen men and eighty-nine women in 1944 to forty-one men and seventy-two women in 1945. (With acknowledgements to the Felbridge & District History Group)

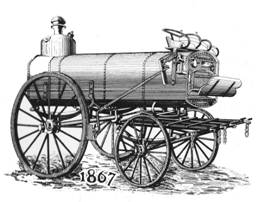

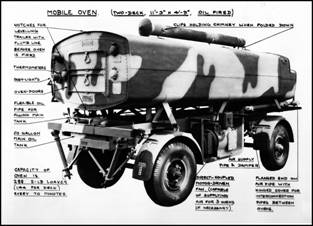

“An army marches on its stomach” is a saying that has been attributed to both Napoleon and Frederick the Great. Following the difficulties of feeding British troops in the Crimea, the British Authorities investigated the introduction of a mobile bread oven and it is understood that experimental trials were held c1858. However, for various reasons the Army did not approve this unit. It is thought that the first approved British pattern was a dry heat unit mounted on a four-wheel carriage (wagon), probably in 1862. With the great success of his stopped-end steam tubes and his father’s history of selling baking ovens to the military it is not surprising that in 1866 Loftus Perkins used this technology to produce a horse-drawn steam oven to feed troops on the march which was exhibited at the Paris Exhibition in 1867.

By 1874, fifty-six of these ovens, known to the British Tommy as the 'Polly Perkins', had been supplied to the British Army, others being purchased by the Prussian and Spanish governments. They served in the Ashanti Wars, the Sudan campaign and the Boer War. As will be seen later, improved models, employing the same method of baking, were still being produced in WW2. It is clear, however, that the military mobile or travelling oven was not a Perkins invention (see here).

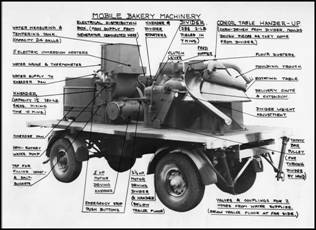

In his book - "Wartime at Baker Perkins Westwood Works" - Ivor Baker remembers - "We were complimented by the Ministry of Supply not only on the quality and quantity of our work but also upon our economical cost of production and we like believing that we merited those compliments. There was, however, one important item of war-making equipment - not in itself an engine of destruction - in which our own particular genius was applied, viz., in the design and manufacture of the Mobile Bakery.

"The problem presented to the designer of a Mobile Bakery can be

very simply stated, but the solution depended upon a wide knowledge of bread-making

such as only we possess and upon our generations of experience in manufacturing

equipment not only calculated, but definitely to be relied upon, to give

a certain result - consistently - economically, and faithfully beyond a peradventure".

"A Field Bakery Unit must be a complete bread-making unit. It must

be equally mobile in the event of attack or of rapid advance. It must

produce loaves, which besides being palatable and nourishing, will stand

up to the inevitable rough handling of Service conditions and finally it

must not falter under usage of a kind that no normal bakery plant ever has

to endure."

Baker Pekins Mobile Bread Making Machinery Unit and Mobile Oven

More information on the Mobile Field Bakeries - including how the individual parts were arranged under canvas to form a complete bakery - can be found here.

Unfortunately, so far we have been unable to locate more than a small amount of paperwork detailing something of the process used to develop Angier Perkins' "Polly Perkins" oven into the complete Mobile Bakery which served the Allies so well in WW2. It was a product of Westwood Works which turned out a total of 205 Bread Making Machinery units (mounted on trailers) and 649 Field Bakery Ovens (mounted on trailers) during WW2. In addition, Baker Perkins delivered 954 of the transportable type of Field Oven known since 1866 as the "Polly Perkins," We expect to be able to add to this record in the next few months.

As an interesting aside, Gordon Steels spent about six months of his apprenticeship wiring up Mobile Bakery Trailers under the direction of Colin (Bocky) Bird. He recalls:

"When finished, under the MoD rules of contract, each trailer would

be inspected independently by a 'Government Inspector' who would sign the form

of acceptance. Unfortunately, the inspector allocated knew nothing about electrical

installations (I believe he was a pre-war insurance collector), and had to be

told that if the needle on the instrument (a

Megger) pointed in a certain position during a continuity check, the electrical

system was sound. He would then sign the document of approval without any idea

whatsoever of what he had signed for. Of course, we would check the installation

before hand ourselves to our own satisfaction and so ensure that the installation

had been safely wired up". (See also "Coping

with Change" - above).

By no means all of the mobile bakeries operating in France prior to Dunkirk

were similar to those described above. Many were equipped with ovens left

over from WW1. These ovens were not equipped with wheels and had to be manhandled

on and off trains and lorries and the doughs had to be made up by hand. Each

oven held 144 - 2lb loaves and there were forty-eight ovens in total, each

making six batches per day or 41,472 loaves - enough for about eighty thousand

men. The ovens were set up in the open air, four to a sub-section - four

sub-sections to a section and three sections to a bakery. Each sub-section

had two marquees - one for the mixing troughs and one as a bread store. (With acknowledgements to "WW2

People's war - Norfolk Adult Education Service)

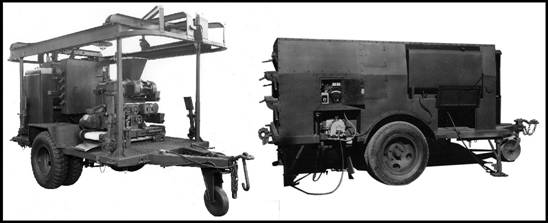

Century Machine Company Mobile Bakery

At the peak of the American boom in 1929, Baker Perkins Co. Inc. bought the whole of the assets of the Century Machine Company of Cincinnati, a manufacturer of bakery equipment for the smaller wholesale baker. During WW2, Century developed a portable field bakery. Made at Saginaw, this consisted of a wheeled oven and bread make-up equipment, not too dissimilar to that made at Westwood. The company was given the Army/Navy Award for its success in manufacturing thousands of these for all of the theatres of war where American troops were serving. This equipment was still being made at Saginaw a number of years after hostilities ceased.

The Baker Perkins Mobile Field Bakeries produced at Peterborough during WW2 were not only used to feed the Troops, but helped to feed the civilian population where commercial bakeries had been put out of action by enemy bombing. Operating in two shifts of eight hours each, the large units were capable of baking the daily bread ration for a full division of 16,000 men. It is understood that the Baker Perkins Mobile Bread Bakery was still being manufactured for some years after the end of hostilities and a number were supplied to Middle Eastern countries.

In 1949, discussions took place with the MoD on the best method of preserving 13 mobile bakeries, following which Baker Perkins Mobile Bakeries were deployed from 1951 to 1992 to local depots by the Ministry of Agriculture for mass feeding in the event of nuclear war or other civil emergency. (Source - The British Museum)

Ready to feed the troops

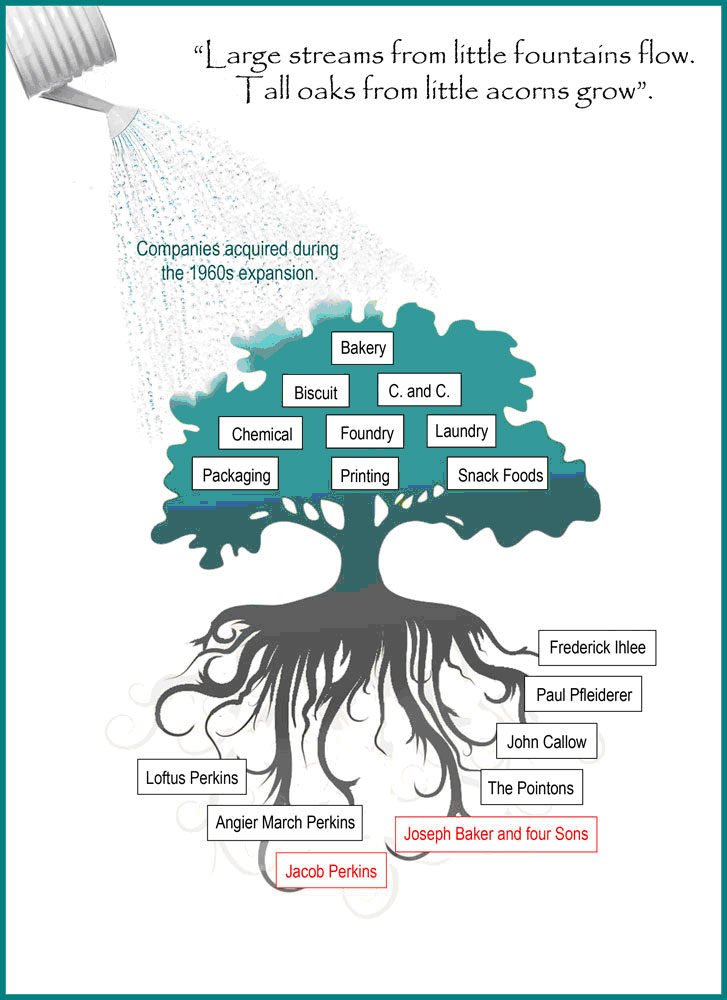

In conclusion, let us return to the first thought articulated in our "Preface" above. The "tree" that became Baker Perkins was fed by many "roots", the company being fortunate in its rich heritage of very strong-minded men shaping the future of the company; men who were concerned for the lot of their fellow men who drove themselves to find solutions to seemingly intractable problems and in doing so changed the lives of millions of people, creating the keystones of food processing technology recognisable to this day.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of the breakthrough in developing a fully automatic bread plant. It is said that if Johnny Pointon or John Callow were able to visit one of today's process engineering companies producing the very latest machinery, he would instantly recognise the similarity with the solutions they arrived at in the opening days of the twentieth century - more than one hundred years ago. Perhaps the same could be said about Paul Pfleiderer and mixing, Angier and Loftus Perkins and baking; and, surely, the Baker brothers and F.C. Ihlee would recognise how much ahead of their time was their approach to motivating the workforce?

Dick Preston - May 2015

PS - Is it wrong - while we bask in the glories of the past - to wish that there existed a Company of these Mobile Bakeries on call ready to be sent to the increasing number of trouble spots - both man-made and "natural" - around the world? Does our past teach us nothing?

RJP

PPS - A large amount of relevant material exists on the internet; inserting "Mobile Bakeries in World War II" into Google yields a significant haul, but you might find that including "RASC" in your search brings many highly detailed personal stories.

It is not acceptable simply to copy large chunks of text, nor should I resort to elegant précis. It is intended to make contact with authors of some of the more interesting and informative memories and seek permission to at least link this website with theirs. It is hoped that this exercise will bear fruit in the near future.

RJP

All content © the Website Authors unless stated otherwise.